Battery Power

Electric cars have always looked like the future, but around the world they are becoming an everyday reality. Can Hong Kong avoid getting stuck in the past or will the city be able to join the electric car revolution?

Not long ago, electric vehicles (EVs) were derided for perceived performance deficiencies, considered unattractive by all but a tiny niche of eco-aware motorists. But even in the most conservative quarters, attitudes have shifted. Now, more than 60 models of electric car are available worldwide. Luxury marques and high-performance carmakers are not only getting in on the act, they’re driving the industry forward.

Arguably, Hong Kong wasn’t designed for EVs. There are many challenges standing in the way of their adoption in the city. On the other hand, no city ever was designed for EVs. When Hong Kong’s narrow streets were laid out, the planners certainly didn’t have mass car ownership in mind either. Every city that has successfully integrated EVs into its public and private transport infrastructure has had to overcome many of the same challenges that Hong Kong faces. Of these challenges, the only ones unique to this city are political, and pernicious. Around the world, city-scale and nationwide programmes are harnessing the benefits of EVs. Rotterdam has 80% of its public transport running on electricity from 100% renewable sources, while London is rushing to overtake it by building Europe’s largest fleet of electric buses. Estonia has become the first country to deploy a network of EV charging stations with nationwide coverage, China has ambitious plans to build a network of 10 million charging stations by 2020. But despite its well-publicised Formula E race, Hong Kong seems a little slow off the mark.

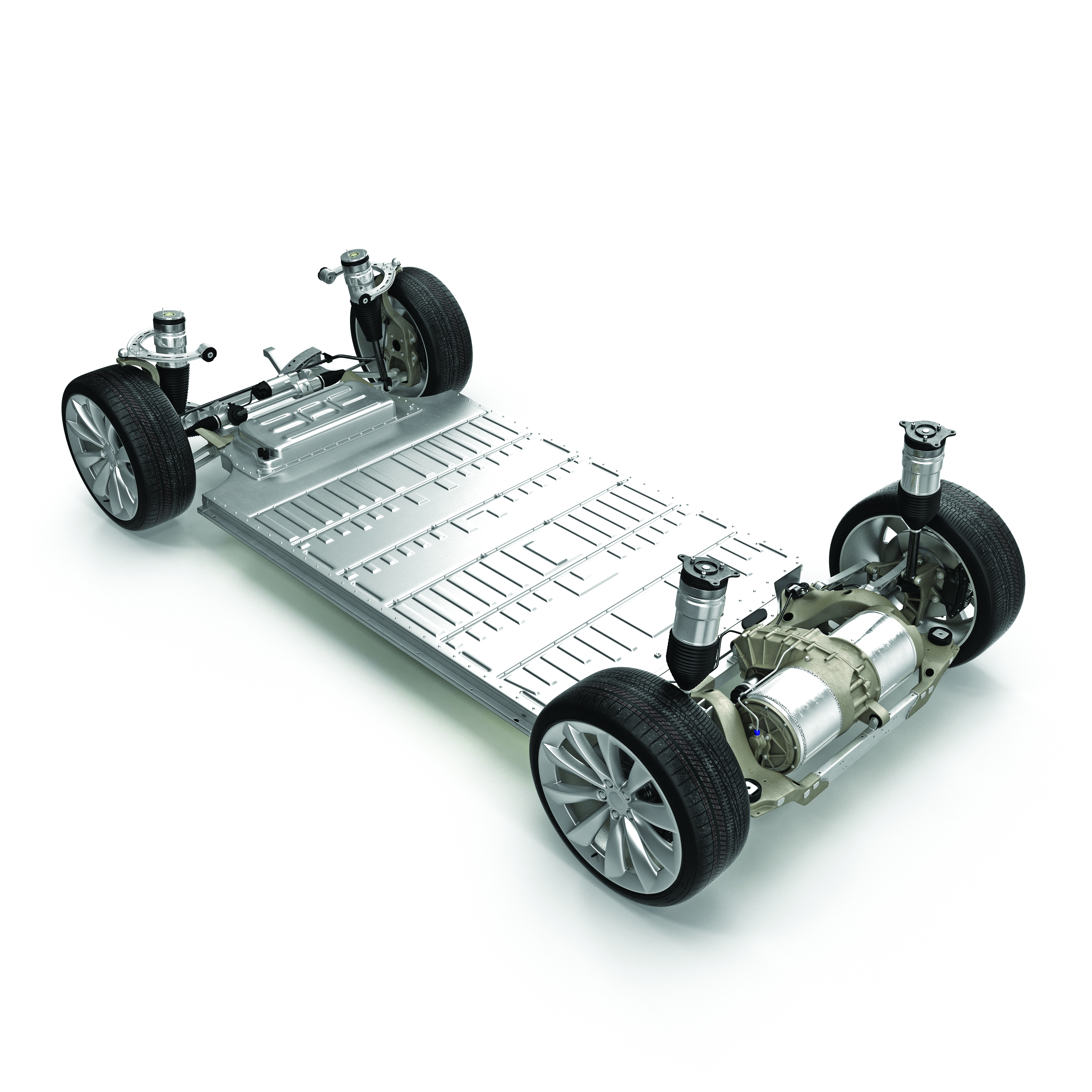

Any city hoping to make EVs a viable part of their transport mix must address the issue of power supply. A major attraction of owning an electric car is the potential to charge the battery at home, thus avoiding ever having to visit a petrol station again. There’s more than one type of EV charger. Standard chargers require the car to be left plugged in overnight, whereas fast chargers can top a vehicle up in half an hour. Obviously, fast chargers are more convenient but need extremely robust power supply infrastructure due to the volume of current they pull.

Both CLP and HK Electric have developed networks of public EV charging stations. In fact, it has been estimated that 90% of the city’s electric car owners rely on public chargers, often with no facility to charge their car at home. Yet the Environmental Protection Department points out public chargers are only intended to supplement owners’ private domestic chargers. So, why are car owners still reliant on public charging facilities?

|

Incentives are in place to encourage developers to include private charging stations in new buildings. But tenants who don’t own EVs tend to be unenthusiastic about paying the extra cost such facilities incur and effectively subsidising their electric car-owning neighbours. This, in turn, makes developers reluctant to install enough stations to meet demand. The same problem discourages operators of private car parks, another potential location for private charging stations. When it comes to developing a network of private charging stations, there is a major question over whether Hong Kong’s power infrastructure could cope with the strain mass adoption of EVs would bring. There is limited spare power capacity in any building, so few locations are suitable for fast chargers and there is a limit on how many cars can be charged simultaneously overnight. According to Ringo Ng, managing director of HKT’s Consumer Group and Managing Director of HKT’s Smart Charge, the best solution is to employ dynamic power management systems to spread the load. Ng is confident this will solve the issue, saying “we foresee a 1:1 ratio on private charger and occupants being the norm in the coming future”. |

However, most of these chargers will require the car to be left on charge overnight. So, for the foreseeable future, the biggest practical benefit of electric car ownership - fast charging - will remain unavailable to most users. But this needn’t be the case forever; the efficiency of cars and batteries improves with every new EV that comes to market. Aside from privately owned cars, diesel-powered buses and light buses produce large quantities of particulates and nitrous oxides and are prone to spend a lot of time in slow traffic or idling at stops. In response, the Environmental Protection Department (EPD) has launched a $300 million Pilot Green Transport Fund. It has supported trials of commercial electric vehicles, hybrids and less-polluting vehicles. By the end of October 2016, the fund had put over 70 electric vehicles on the road. |

|

This all represents a valiant effort. But trialling new technologies counts for little unless the trials lead to development and implementation of new technology. Unfortunately, Hong Kong’s high profile electric bus trial ended after a series of relatively minor setbacks; a simple glitch with the stop bell causing the new buses to be shelved indefinitely last year. Similarly, a two-year scheme by BYD - the world’s biggest electric carmaker - which aimed to introduce electric taxis to Hong Kong met resistance from drivers despite massive investment and huge potential benefits. The trial was branded ‘a failure’ by BYD’s General Manager. The main reason for the drivers’ concerns? Inadequate charging infrastructure.

Given the economic pressures on taxi drivers caused by Hong Kong’s unique licensing system, these concerns are understandable. The majority of Hong Kong’s taxi drivers rent the vehicle on a shift basis from the owner of the taxi licence. Neither drivers nor licensees are likely to willingly accept the loss of revenue that would result from leaving their car charging for long periods when the current LPG models can potentially run round-the-clock. Furthermore, with the number of taxis in Hong Kong fixed at 18,138 for the past 13 years, and unlikely to be increased, the city can little afford to have vehicles spend a significant proportion of their time off the road, charging. As long as there remains little political will to overhaul the taxi licensing system, these obstacles to the adoption of electric taxis are unlikely to be overcome.

|

So now, even the Environmental Protection Department has little hope that electric vehicles are ‘a good fit’ for Hong Kong’s public transport. And if the EPD isn’t advocating to put clean vehicles on the city’s streets, who will? With so many challenges already facing the adoption of EVs in Hong Kong, an additional setback has come with the government’s decision to raise the First Registration Tax (FRT) exemption for electric cars. Until the end of March 2017, electric cars were fully exempt from FRT, but the exemption now only covers part of the tax payable. The FRT exemption was, in part, intended to curb the increase in polluting vehicles on Hong Kong’s roads. However, exemptions are available not only on electric cars but other types of more efficient vehicles, including petrol and diesel-powered models. The upshot has been that the concession on FRT for less-polluting vehicles mitigated the measure’s impact on the overall growth in vehicle numbers, while high taxes on other types of vehicle encouraged owners to keep their older, more polluting cars on the road for longer, rather than replacing them. In short, old, dirty vehicles remain stuck in the same slow-moving traffic. |

For the past two decades, this was the status quo. As long as EVs remained uncool, their sales making up a small fraction of overall vehicle sales, the electric car FRT exemption had minimal impact on tax revenue so there was little incentive to raise the exemption. The raising of the FRT exemption targets buyers of electric cars seen as desirable luxury options - the models making EVs fashionable. The decision to end FRT exemptions on electric cars looks a lot like killing the goose that laid the golden egg. The bottom line is that both consumers and the city’s authorities appear resistant to technology seen as new and unproven. But this is due to a misconception. Anyone who commutes by MTR is familiar with using a high speed, reliable EV every day. Furthermore, some of the earliest cars ran on electricity. The limited range of early EVs made them uncompetitive against fossil-fuelled models; the development of long-distance motorways during the 20th century led to more people making longer journeys, and early electric vehicles just couldn’t keep up. But battery technology is lightyears ahead of where it was then. Hong Kong’s geography, its dense population centres and confined territory mean few drivers make journeys that would challenge the range of modern EVs. And the instantaneous torque offered by an electric motor makes Hong Kong’s steep winding roads a breeze for electric vehicles. |

|

If any city could benefit from zero tailpipe emission EVs, it is Hong Kong. Thousands of idling engines on narrow streets, hemmed in by tall buildings creating a toxic environment. In the 10 years from to 2013, the total number of vehicles on the city’s roads grew from 524,000 to 681,000 while traffic speeds dropped 11 per cent. Some of the busiest roads recorded average speeds of 4-5 km/h, barely walking pace. In this atmosphere, the adoption of clean EVs would have an immediate positive impact on public health.

Resistance to new technology seems inevitable, regardless of the massive potential benefits of its adoption. But none of the barriers to the adoption of EVs in Hong Kong is insurmountable. Around the world, the tide is turning in favour of the electric car. And Hong Kong will need to find ways to keep up.

Others

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

Robot Society

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

We need to talk about 'Tesign' - Design starting with Tech

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

Game Changers

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

Hyper-reality

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

When Art, Fashion and Music Collide

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

Designers Making a Difference

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

Small City, Big Data

最新動態 | 1 September 2017

Making a Mark

最新動態 | 1 September 2017