Shenzhen’s Shifting Fortunes

From sleepy border town to booming manufacturing hub to design city – Shenzhen is continually transforming itself as it spearheads China’s passage to an innovation-based society.

When Shenzhen was named a Unesco City of Design in 2008 ahead of its more illustrious urban counterparts of Beijing and Shanghai, eyebrows were raised. This frenetic new metropolis, rolling over former fishing villages just north of Hong Kong was known as, at best, a manufacturing hub and, at worst, a marketplace for cheap design imitations. Workers flooded south to the Pearl River Delta to fuel its industrial base. Shenzhen was decried as the ‘Factory of the World’, a place where anything, from handbags to electronics, could be made, or copied, cheaply and at lightning pace.

Today, it is a different story. Criticism has morphed into admiration as Shenzhen assumes the mantle of one of the world’s largest manufacturing centres. It enjoys a high-tech prowess approaching that of Silicon Valley but with the added advantage of having production on its doorstep. It is still growing – up to 12 million people at the last count – with striking skyscrapers announcing its presence as a Chinese city of international importance. Migrants are now likely to be skilled, entrepreneurial and often foreign: Chinese from Hong Kong or Taiwan as well as Westerners armed with ideas, expertise and a desire to make money. That early vision as a home of creativity and design is finally being realised.

“Ours is a very young city,” said Xu Chongguang, deputy secretary general of the Shenzhen municipal government, last year. “It is also a city that is open to new ideas.” Ole Bouman, the Dutch director of Design Society, a not-for-profit cultural foundation established in the city’s Shekou district, concurs. “This is still a new city. It’s more existential than Beijing and Shanghai and asking questions is second nature here,” he said in a 2016 interview with the South China Morning Post.

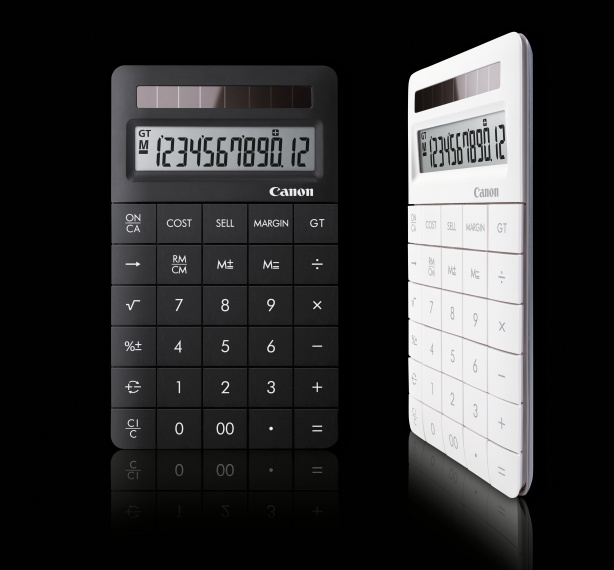

Since the border town of Shenzhen, population circa 30,000, was chosen as China’s first special economic zone in 1980, local government and business have worked hand in hand to build something substantial from practically nothing. The city serves as the country’s model for opening up to the world and becoming an economic powerhouse. “The supply chain is the most important thing that makes Shenzhen the capital of manufacturing,” opines Red Dot Award-winning product designer Allan Zhang of Crazybaby, a maker of earphones. “There are a lot of satellite cities around, such as Dongguan, Huizhou and Zhongshan, and they can form a complete supply chain providing almost everything from raw materials to computer components at very low cost.”

The factories and supply chain were built first, and the concept of modern Chinese design germinated in the back garden of the production lines. As arts professional Brendan Cormier, who moved to Shenzhen in 2014, writes, “For years the popular image of Shenzhen was not pretty. Millions of Chinese immigrants resettled here to take up low-wage factory jobs, often leaving their families behind. Global news reports about pollution, poor working conditions and worker suicides exacerbated the city’s image as an anonymous and brutal place.”

Shenzhen’s evolution from these raw beginnings to a more sophisticated final product in just a few decades would not have been possible without government support and a receptive, energetic population. The framework for a design city was built with the import of ideas and professionals. The Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture was launched in 2005 (with Hong Kong’s participation two years later it became the Bi-City Biennale) more recent annual initiatives include Shenzhen Fashion Week, Shenzhen Design Week and the Shenzhen Design Award for Young Talents.

|

Luring foreign talent and investment to the city on a permanent basis has been made possible by a generous raft of government grants, concessions and subsidies. In 2011 the ‘Peacock Initiative’ offered awards of up to RMB 100 million to start-up teams and firms in IT and emerging industries. Visa applications have been simplified and accelerated and in 2017 subsidies of up to RMB 3 million were available to foreign holders of Shenzhen permanent residence permits. In addition, foreign nationals and migrants from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan can now benefit, alongside locals, from the Shenzhen Housing Accumulation Fund. Numerous tax concessions, particularly for high-tech companies, have also made the city more advantageous to non-nationals. These incentives, coupled with cheaper rents, have seen Hong Kong entrepreneurs crossing the border to Shenzhen’s Qianhai free-trade zone in increasing numbers: at least 85 small firms have set up in the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Youth Entrepreneur Hub there. Dreams of becoming the next big startup, in the wake of Shenzhen’s super-success stories Tencent, Huawei, drone maker DJI, and Seeed Studios (whose founder Eric Pan was on the cover of Forbes Chinese edition in 2015 as one of 30 entrepreneurs under 30) can come true. The Shenzhen government offered tech start-ups US$202.9 million in funding in 2014 – while only US$33.7 million was on offer in Hong Kong – and eligible companies located in Qianhai paid 15 per cent corporate tax, compared to 25 per cent outside the zone and 16.5 per cent in Hong Kong. Labour is also more affordable, and as one such recent cross-border migrant put it, “The people are down to earth”. |

“People in Shenzhen don’t have the burden of history, they want to create something of their own,” said Doreen Heng Liu, a curator at Shenzhen’s 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture. “It’s fast adapting compared to other cities in China. Young people really feel at home here because Shenzhen gives them a lot of opportunities.”

An estimated 6,000 design firms employing some 100,000 designers flourish in this land of innovation and opportunity. Shenzhen’s cultural and creative industries are said to be growing at an average annual rate of 25 per cent and two years ago their share of the city’s gross domestic product had reached almost 15 per cent. With its manufacturing base secured, design is now adding value. The full spectrum of design industries is present, from fashion, products and toys to architectural, interior and digital design.

The 800 Chinese fashion brands in Shenzhen, China’s largest producer of women’s clothing, employ some 30,000 designers. Mayor Qu Xin stated in the China Daily newspaper last year that his city has become the most creative fashion hub in China. Running the gamut from commercial to edgy, names such as Marisfrolg, Haiping Xie, Ming Yue He and Odbo have caught the imagination of fashion writers at home and abroad. Lai Rui of Shenzhen favourite La Pargay won the China Fashion Award in 2015.

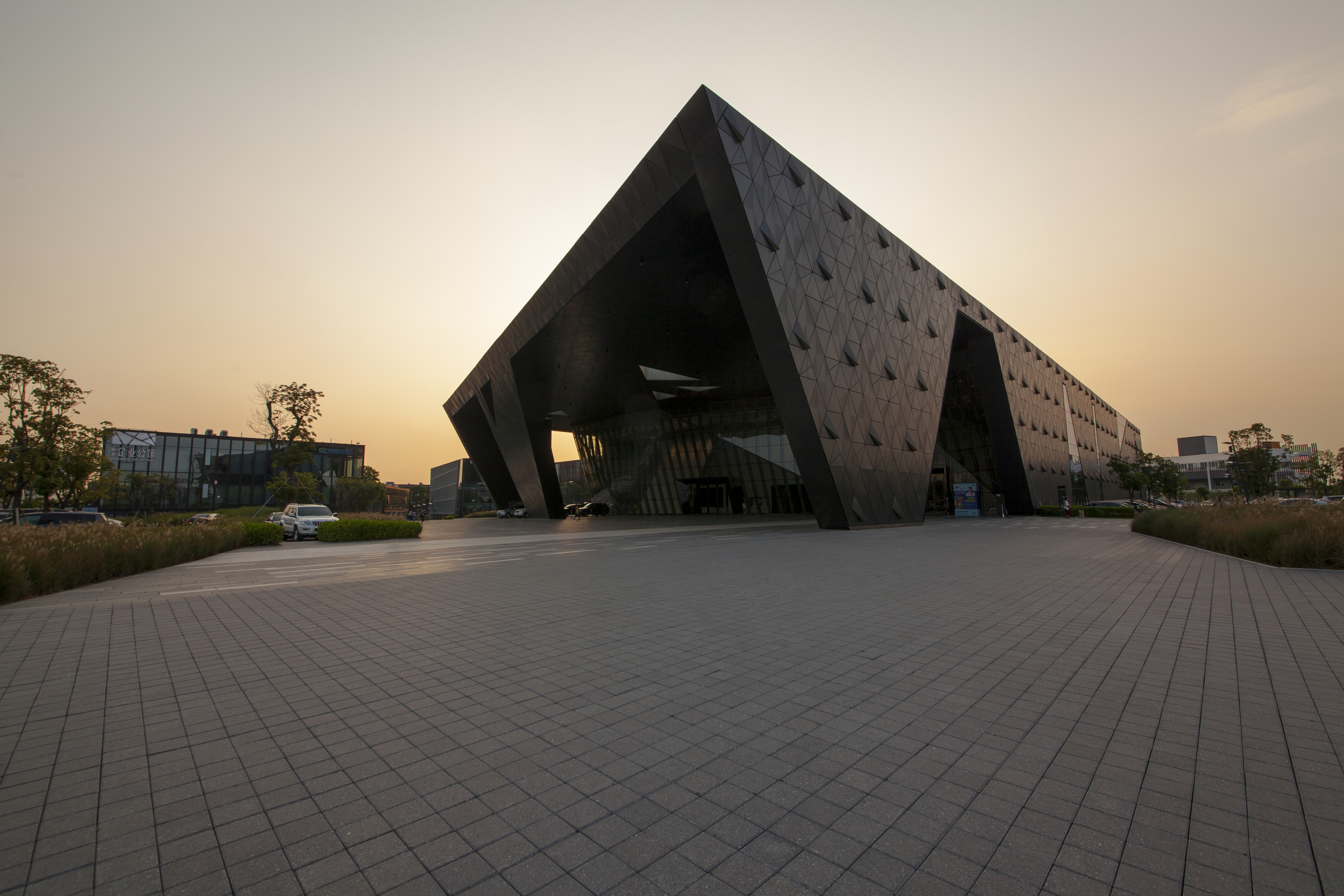

Shen Yongfang, president of the Shenzhen Garment Industry Association, proclaimed in an interview last year “Working on the internationalisation of Shenzhen brands is my life’s mission”. With Marisfrolg founder Zhu Chongyun taking over Krizia in 2014, and Shenzhen Ellassay Fashion acquiring French brand Iro and a majority stake in Vivienne Tam’s China brand rights this year, his job is getting easier. Ellassay chairman Xia Guoxin stressed that Tam will assemble an international design team in the city to create pieces that resonate with China’s young generation. With municipal government support, designers regularly present their work at international design festivals and fashion weeks. Zheng Qu, director of London’s China Design Centre, has lauded the Moon Lamp, designed by Shenzhen-based Jerry Huang of EY-Products, as an example of a sea change in China, “The emphasis in Chinese design used to be on strong traditional elements. Now it’s more about abstract concepts and functionality,” he said before the 2015 London Design Festival. “Designers from China are starting to understand that they have to tell a story with their work, it can’t just be about the product or brand.” The V&A Museum’s Luisa Elena Mengoni, now based in Shenzhen, is similarly encouraged watching the city’s young designers come into their own, “There’s been a graphic design industry here since the 1990s to serve local factories, but individuals like Huang Yang represent the new generation and they are doing such interesting things.” . Huang Yang Design, located in trendy OCT-Loft, is known for its work with Chinese artists as well as international brands such as Uniqlo. For the most part, it is foreign talent that is transforming the Shenzhen skyline. Prestigious architectural design firms are being commissioned to create statement buildings that underline the city’s rise in the eyes of the world. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange was the brainchild of Dutch firm OMA, co-founded by Rem Koolhaas; another Dutch architect, Mecanoo, will build 12 stepped skyscrapers around a Shenzhen park. Shenzhen international airport Terminal 3’s distinctive hexagonal skylights are the work of Italian practice Fuksas. Last year US firm Morphosis topped out a 350-metre-high tower, dubbing it the tallest steel building in China.

|

|

|

The best-known local architect practice is Urbanus, which came to Shenzhen early, in 1999. “[China’s] economy had just begun to recover from a five-year recession; it was the dawn of the grand and rapid construction wave,” said co-founder Liu Xiaodu in a 2015 interview with Arch Daily. “Our first project in Shenzhen made us discover this new immigrant city; young, open and energetic but with a flat social structure. At that time there were neither strong domestic architectural firms, nor foreign design firms that rushed in to take the lead. It was a situation with no competitors and we found our space easily.” Nine years later, a lot of hope is riding on Shenzhen to become a new design powerhouse, opines Cormier. “After decades of serving as the factory of the world, the city now boasts a robust infrastructure of workshops, supply chains, and know-how, a lucrative attraction for young entrepreneurs and makers.” There is no doubt that China’s modern-day shift to an innovation-based society and economy is being spearheaded by Shenzhen. The evolution from manufacturing hub to design city may not have reached its conclusion quite yet, but the road forward has been paved. |

Others

Latest News | 1 March 2018

Exporting Shenzhen’s design culture

Latest News | 1 March 2018

In Praise of Silk: Fashion from China National Silk Museum Across Time

Latest News | 1 March 2018

KEEP WATCH-ING

Latest News | 1 March 2018

Into the Laboratory

Latest News | 1 March 2018

Different Paths

Latest News | 1 March 2018

Are you working well?

Latest News | 1 March 2018

Adventures in Space

Latest News | 1 March 2018

The Chain

Latest News | 1 March 2018

Future-facing Retail